Market Intervention and Regulation

Market regulation may be justified under some circumstances to increase economic efficiency.

Because supply and demand interact to determine prices, it might create an illusion that the market is naturally self-regulating. The difficulties encountered by formerly Eastern Bloc countries in setting up market economies illustrate that well-functioning markets do not spontaneously emerge. In fact, without well-defined property rights, physical and institutional market infrastructures, and the existence and enforcement of market-related laws, only the most rudimentary transactions can take place.

But even when such laws and institutions relating to market operations exist, the market outcome might still be in conflict with the perceived public interest. Prices might be too high or too low, output level might be too high or too low, or income might be too unevenly distributed.

All the unhappiness about market outcome provides excuses or bases for market regulation. There are clear purely economic grounds for market regulation in the following situations:

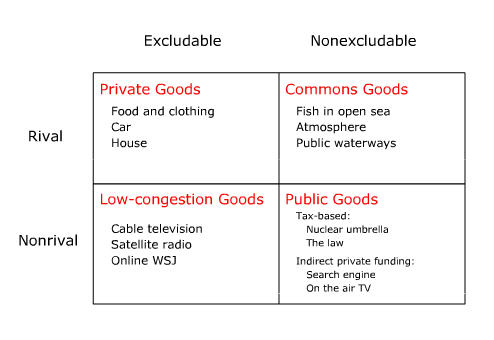

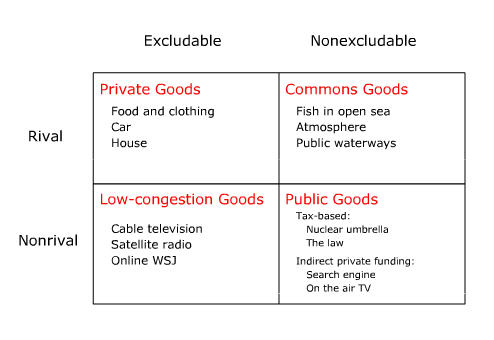

• The market is unlikely to produce certain jointly consumed goods that are desirable but are non-excludable to non-payers (public goods) – such as national defense.

• The property rights of some commons resources are not definable because of high enforcement cost (commons goods) – air pollution.

• Consumers are unlikely to have adequate information to evaluate the quality or efficacy of some products – prescription drugs.

• One party of the transaction is likely to have more information and power than the other (asymmetric information) – lemons.

• Collusion among oligopolistic firms to raise prices and restrict output of commodity products (antitrust laws).

But a lot of market interventions and regulations are poorly implemented leading to high cost and market rigidity. For example, antitrust actions to preserve competition might end up protecting inefficient incumbent competitors instead of protecting consumer interests.

Government market intervention could also be politically swayed due to special-interest lobbying (see The Logic of Collective Action). The anti-market bias of public opinion (see Special-interest Secret) is strengthened by the unfair distribution of collective gains from market liberalization (see Efficient But Not Fair).

Glossary:

- regulationGovernment actions to temper the adverse effects of uncontrolled market activities.

- collusionAttempts or agreements among cartel members to restrict output and raise prices.

- commons goodA commons good is one that is available to all potential users but subject to congestion. A popular public beach is a commons good prone to traffic congestion in summer.

- efficiencyA state when the marginal social benefit of an activity is equal to its marginal social cost.

- property rightThe control over the use or transfer of a resource. Property right is conducive to efficient use of scarce resources as owners have an incentive to maximize their long-term returns.

- asymmetric informationInformation that is not equally shared between parties in a transaction. For example, the seller of a used car is likely to know more about the quality of the car than an average potential buyer.

- antitrust lawsLaws intended to protect consumer interests and preserve market competition.

- public goodsGoods that are not subject to consumption rivalry but cannot easily exclude non-payers either by design or due to technical difficulty.

Topics:

Keywords

antitrust, asymmetric information, commons goods, cost effectiveness, intervention, lemons, market, pollution, prescription drugs, public goods, Regulation